Japan, South Korea among top donors to replenish Green Climate Fund

The U.N.-backed Green Climate Fund (GCF) secured over US$9 billion for 2024-2027, falling short of expectations, with global pressures mounting on the world’s top emitter China, to start contributing to the international climate finance mechanism.At the replenishment conference held Thursday in Bonn, Germany, 25 donor nations pledged $9.32 billion, with at least five more countries expressing intention to give to the fund set up to help poorer countries deal with the challenges of climate change, said Mahmoud Mohieldin, the facilitator for GCF’s second replenishment.

The contributing nations “recognize that addressing the climate crisis is a shared responsibility and that developing nations are not alone in this fight,” said Mafalda Duarte, GCF’s new executive director.

GCF had raised more than $10 billion in 2014 and 2019 each time and were planning to raise up to $15 billion this funding round. Organizers said Thursday they expected the amount to grow at the COP28 climate conference in Dubai later this year.

Japan contributed 165 billion yen (US$1.1 billion), the highest amount from Asia, while South Korea announced US$300 million.

Other Asian countries to pledge include landlocked Mongolia, which announced to give US$100,000. Previous donors, Indonesia and Vietnam, have not returned to replenish their contributions.

China, the world’s biggest emitter, has never contributed to the GCF.

A general view shows the plenary hall during an international replenishment conference for the United Nations Green Climate Fund in Bonn, Germany, Oct. 5, 2023. (Credit/Reuters)

A general view shows the plenary hall during an international replenishment conference for the United Nations Green Climate Fund in Bonn, Germany, Oct. 5, 2023. (Credit/Reuters)On Thursday, Germany’s Development Minister, Svenja Schulze, called on China and oil-rich Gulf states to contribute to global climate finance.

“We accept our responsibility and do our fair share,” she said after the conference. “On this basis, we can also ask others to do their fair share too.”

Last month, US climate envoy John Kerry also asked China to contribute, saying “if they want to be global economies, they need to act like global economies.”

The highest amount this time was announced by Germany, who said it would give US$2.2 billion, followed by the United Kingdom with US$2 billion and France with US$1.7 billion.

Australia announced it will rejoin the fund, which it left under a previous right-wing government in 2018, with a “modest contribution” to be announced later this year.

The United States, a co-chair of the GCF’s board, said it is still “working on its announcement,” given the challenges faced in D.C. to secure Congress’s approval for substantial global climate finance contributions.

Earlier in the year, President Joe Biden allocated US$1 billion from the initial U.S. commitment, adding to the US$1 billion pledged during the Obama era. However, former President Donald Trump was against any global climate funding.

The pledge is ‘short of expectation’

Operational since 2015, GCF is the world’s largest climate fund with projects worth US$12.8 billion approved, less than a third of which are in 83 Asia-Pacific specific projects.

Many experts and climate activists expressed disappointment at the amount raised Thursday, especially since Duarte has announced plans to disburse US$50 billion by 2030.

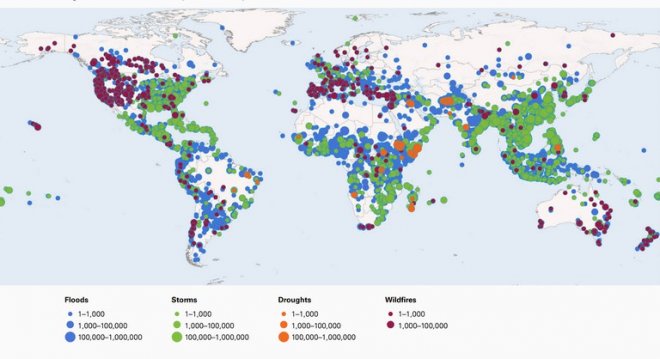

“As climate-driven floods, droughts, and heatwaves devastate communities, the status quo is simply not enough,” said Shuang Liu of the World Resources Institute.

Another prominent climate activist said the GCF pledging conference fell “short of expectations,” denouncing wealthy countries for their “indifference.”

“While Ireland’s 150% pledge increase is praiseworthy, the tepid commitments—or outright stagnation—from nations such as Japan and Norway are deeply concerning,” said Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network International.

Countries like Sweden were sidestepping their obligations “by urging developing nations to contribute,” he said. “The silence of the United States, even as it participates on the GCF Board and shapes policies without meeting its financial obligations, is glaring and inexcusable.”

At the pledging event, Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown said while “money is not everything… [it] does go a long way to addressing some of these impacts.”

He said at least US$100 billion in funding is required each year for climate action, which is less than 0.1% of current global GDP at US$105 trillion. Meanwhile, “fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 were a trillion dollars.”

“That really does show the stark difference between funding that’s being made available to address the issues of climate and what is being put in place into an industry that is continuing to push carbon emissions out into the world,” Brown added.

Many vulnerable countries have said GCF, and similar funds, are tough to access due to their complex and resource-consuming processes. Even GFC conceded in an April internal review that the convoluted process puts its reputation at stake.

Duarte “faces the immense task of not only expanding its financial resources but also refocusing on adaptation and simplifying access for developing countries,” Singh told Radio Free Asia on Friday.

More than half of GCF’s allocated funding is in the form of loans and equity, while the use of grants has decreased from 53% in 2017 to 37% last year.

“We have to borrow the money from the countries that actually cause the carbon emissions to protect ourselves from the impacts. Again, for me, that is morally wrong to do,” Brown said Thursday.

Singh also said that loans instead of grants “places an additional debt burden on developing countries.”

“As these nations confront vital development needs and increasing climate impacts, this imbalance is a profound injustice.”

Edited by Elaine Chan and Taejun Kang.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

|

本篇 |

不想錯過? 請追蹤FB專頁! |

| 喜歡這篇嗎?快分享吧! |

相關文章

AsianNewsCast