Interview: Pol Pot was 'strikingly charming...until we began to talk'

Nate Thayer, an American journalist who was the last Western correspondent to interview the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal leader Pol Pot, died early this month in Massachusetts, aged 62. In September 2006, Sok-ry Som and Kem Sos of RFA Khmer interviewed Thayer, who had spent years in the jungles of Cambodia chronicling the Khmer Rouge’s 1975-1979 rule, during which an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians perished. The conversation with Thayer--who discusses his interviews with Pol Pot and other senior Khmer rouge figures including No. 2 leader and chief ideologist Nuon Chea, Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Duch, commandant of the notorious Tuol Sleng (S-21) torture prison, and senior military leader Ta Mok--has been edited for length.RFA: If I am correct, you were the only outside journalist able to get access to the Khmer Rouge camps and interview Pol Pot, Ta Mok and Duch. How did that happen?

Thayer: I was the first outsider to gain access to Pol Pot after he was arrested and tried in 1997. It was a long process of years of accessing sources within the Khmer Rouge, within the Thai military – a variety of other sources that slowly I built relationships with the Khmer Rouge from the bottom up.

RFA: What was your impression of when you met him firsthand?

Thayer: He was strikingly charming with a gentle, soft voice, very charismatic; very likable -- until we began to talk. And what he said was that essentially he had no remorse for anything that he had done in Cambodia, that he had done more good than bad. His constant theme was that they had made mistakes, but they"d saved the country from becoming taken over by Vietnam. And that was what he repeatedly went back to. He clearly died without accepting that he had done more bad than good for his country.

RFA: And what kind of questions did you ask him?

Thayer: Many questions. It was a two hour interview, but when I began it, we didn"t know how long it would take. And we said it might only be a few minutes. So I wanted to get to the questions that that most Cambodians wanted to hear, which was, are you a mass murderer and are you sorry, or do you have any regrets for what you did to your country? So I started out with the questions of his culpability and crimes against humanity and genocide, failed central policies while he was in power.

An undated photo of Cambodian dictator Pol Pot

An undated photo of Cambodian dictator Pol Pot with former Khmer Rouge foreign minister Ieng Sary

was found in the guerilla leader’s former stronghold of Anlong Veng by an Agence France-Presse reporter on March 28, 1998. The picture was believed to be taken in China in the late 1970"s, according to Pich Chheang, former Khmer Rouge ambassador to China. Credit: AFP![]()

RFA: Did you ask him why did they evacuate the cities? Why he forced people to leave the cities in June 1975?

Thayer: Yes, I asked him and I asked him after noontime consumption, uh, also the same questions. And they were convinced that there was a plot to destroy them. And that was the primary reason.

RFA: And did you ask him about that part, about Tuol Sleng prison?

Thayer: I did. And he claimed that he"d never heard of it, and it was probably the most difficult part of the interview in terms of confrontation, because it was clear from the documentary evidence that he was, in fact, in charge of the Khmer Rouge killing machine. And he denied that … that he had ever heard of Tuol Sleng and that he had any involvement at all. But at the same time, he admitted to killing people but justified it as them being part of the Vietnamese plot to overthrow (them).

RFA: How was the interview atmosphere? Did he appear friendly to you or fearful to you? Secondly, how about the accuracy? How did you feel in that time? Did what he said sound reliable and accurate to you?

Thayer: He came across as very genuine. Like any top political leader, he had great charisma and I had great sympathy for him. He was an old man. He was sick. He was, in fact, dying. And that was quite clear. He was clearly trying to draw sympathy towards himself and his political movement to put into place in history the way he"d like it to be viewed.

RFA: Back to the evacuation of cities. Did they think about the consequences?

Thayer: No, they didn"t think of the consequences. And then that was one of the perennial problems with Khmer Rouge is that they only thought of the benefits and not the consequences to some of their actions. And they were absolutely concerned that there were enemies everywhere. There were enemies within the population, within their own ranks. If there were spies in the employ of foreign intelligence agencies that were trying to overthrow them. And they were absolutely convinced that the most important thing for them to do was to protect the leadership of their movement and to keep them in power and keep them safe and keep them from being killed. And they took every measure possible to ensure that without thinking of the consequences. And when they evacuated the cities, Pol Pot told me that that there were two coup plots in process at that time to overthrow them: one by Lon Nol after a meeting in Bali in May of 1997 and another from within the Khmer Rouge ranks themselves, and claimed six different coup attempts against him during his years in power. And he was absolutely concerned that there were enemies within the ranks, within the army, in the employ of the Vietnamese, and in fact, in the employ of all three, the KGB, the CIA and Vietnamese at the same time working together against them. In fact, it was his entire focus on the Vietnamese taking over Cambodia that created his policies, that created so much suffering within the country, that weakened the country so much that in fact allowed his worst nightmare to come true, that the country was so weak that it became vulnerable to a Vietnamese invasion. And it was his policies of terror and incredible suffering that, in fact, made the country weak enough to allow what he feared the most to come true. You could argue that it was Pol Pot who made Cambodia in a position to become a satellite of its historical enemy. And it was something that was, I think, almost too painful for him to accept himself, that it was his own policies that created the conditions that allowed Cambodia to disappear. When he, in fact, took credit for saving the country from disappearing from the face of the earth.

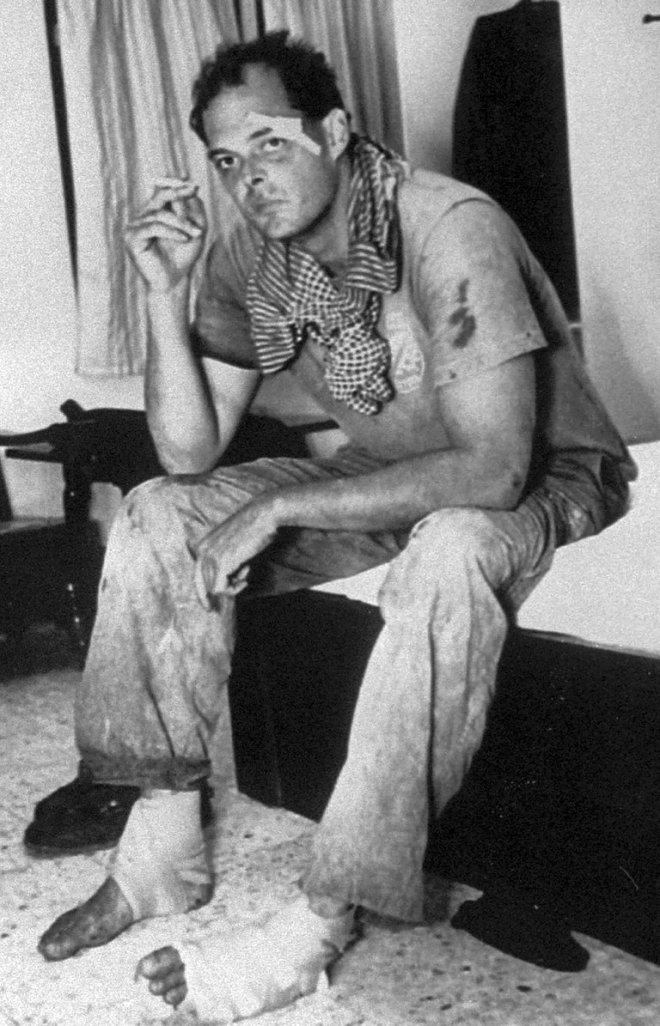

![]() American journalist Nate Thayer sits bandaged in a hotel room on Oct. 15, 1989 in Aranyaprathet, Thailand, after he was injured in a land mine explosion while returning from Cambodia. Credit: Associated Press

American journalist Nate Thayer sits bandaged in a hotel room on Oct. 15, 1989 in Aranyaprathet, Thailand, after he was injured in a land mine explosion while returning from Cambodia. Credit: Associated Press![]() RFA: Why didn"t the many reported coup attempts against Pol Pot succeed? What happened?

RFA: Why didn"t the many reported coup attempts against Pol Pot succeed? What happened?

Thayer: Anyone who voiced any opposition to it, however small, even within the top leadership of the Khmer Rouge, was immediately deemed an enemy and arrested and killed. When the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, there were 22 members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. By the three years, eight months and 20 days before they were overthrown, 18 of those 22 were in fact killed and targeted to be killed by Pol Pot himself. The vast majority of the victims of execution of the Khmer Rouge were, in fact, Khmer Rouge cadre themselves, and it was the purifying of the forces within the Khmer Rouge that were the main targets of Pol Pot. For every one person executed, probably seven died of starvation or overwork, and the executions were targeted mainly among Khmer Rouge cadre. And it created an atmosphere of immense fear throughout the country that anything, any small thing that was done that might be perceived as being against the regime was tantamount to death.

RFA: What did you ask Ta Mok?

Thayer: Well, about, for instance, his involvement and knowledge of Tuol Sleng and taking responsibility for the great suffering that occurred during the years that he was in power. Ta Mok was an uneducated military commander, and he was a peasant and a military commander who spoke very straightforwardly. He was the first Khmer Rouge leader ever to acknowledge in an interview with me the fact the Khmer Rouge had, in fact killed hundreds of thousands and that he regretted it. And then it was it was a mistake and it was wrong. Although he denied any personal culpability. Duch was the first Khmer Rouge leader that I"d ever interviewed who in fact took responsibility for what he had done. He acknowledged thoroughly that he had been responsible for the deaths of thousands of innocent people and felt great remorse. And he was the only leader. And I interviewed all the Khmer Rouge top leaders who ever acknowledged that he, in fact, was responsible for the deaths of innocent people and was willing to admit it and willing to take the consequences of it.

![]() A Khmer Rouge soldier waves his pistol and orders store owners to abandon their shops in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 17, 1975, as the capital falls to the communist forces. Credit: Associated Press

A Khmer Rouge soldier waves his pistol and orders store owners to abandon their shops in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 17, 1975, as the capital falls to the communist forces. Credit: Associated Press![]()

RFA: Could you tell us a little bit about Tuol Sleng from what you learned about it?

Thayer: Well, Duch was very clear and many, many hours of interviews, very detailed and precise about the organization of S21. He reported directly Son Sen and to Nuon Che. Son Sen as the military representative within the Khmer Rouge and Nuon Chea as representing the Communist Party. And every interrogation that they made, documents were photocopied and sent to both Nun Chea and Son Sen. And Nuon Chea, took over the entire administration of S-21 in 1978 while the war was beginning to grow against Vietnam and such and went on to take control of leadership of the war against Vietnam. And it was very clear from Duch that Nuon Chea was directly responsible for the killings of thousands and thousands of innocent Cambodians and had no regard for interrogation processes or for any kind of even remote respect for human rights against his own people.

RFA How about the killings in Tuol Sleng?

Thayer: Yes he did. He went into great detail. And first the prisoners were interrogated, sometimes for many, many weeks, sometimes for months. And once they were finished of value of interrogation, they were taken to be killed at Chouerng Ek, seven miles from from S-21. And he made it very clear that it was the rules of the Communist Party, that anyone who was arrested would die, that there was no question about that anyone who was ever arrested would be killed. And he looked at the arrest of people from, I think, his scientific background as a mathematician, where he never questioned the correctness of the party, that anyone who was arrested was guilty. But those people arrested included the wives and children and family members. Duch was very remorseful. He broke down into tears about all of the women and children who he had ordered killed.

RFA: What would make him confess all these things to you?

Thayer: You know, Duch was a fanatic and he was a fanatic in his training as a mathematician, as a member of the Communist Party, and later, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, as a born again Christian. And the tenets of fundamentalist Christianity are that in order to be saved, that you must confess your sins and you must seek salvation through redemption and confessing your sins. And he was a born again Christian, then a fanatic Christian. And he believed that in order for him to go to heaven that he would have to take responsibility for his actions. And that was, in my view, why he was willing to confess, because he thought that it was according to the Bible, that he would have to take responsibility for his actions.

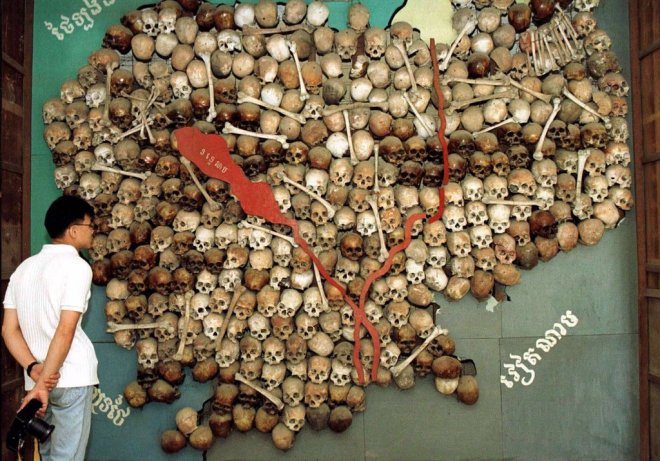

![]() A visitor stands before a map of Cambodia made from the skulls and bones of victims of the Khmer Rouge"s brutal 1975-79 "killing fields" regime at Tuol Sleng in Cambodia, June 23, 1997. Credit: Reuters

A visitor stands before a map of Cambodia made from the skulls and bones of victims of the Khmer Rouge"s brutal 1975-79 "killing fields" regime at Tuol Sleng in Cambodia, June 23, 1997. Credit: Reuters![]()

RFA: Very few people made it out of Tuol Sleng.

Thayer: There were seven people out of 16,000 who survived, and those seven were ones that were left over when the Vietnamese took control. There were there were only two people that Duch ever freed. One was a Frenchman by the name of Francois Bizot, and another was a Khmer Rouge cadre who was misidentified. But Duch said repeatedly that it was the policy of the party. Whoever was arrested must be killed, and there was no question about that.

RFA: Is there anything else you want to add about these three important figures that Cambodian people should know?

Thayer: If we were able to contribute anything, it was that we were able to get some of the facts about what happened during the Khmer Rouge time. As a matter of public record and that the efforts of the press were far more successful than the efforts of any government to at least have Cambodians be able to have some knowledge from those who were in charge of those terrible years of suffering under the Khmer Rouge of what happened, and whether their leaders felt, in fact, any remorse or took responsibility for their terrible failed policies while in power.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

RFA: Did you ask him why did they evacuate the cities? Why he forced people to leave the cities in June 1975?

Thayer: Yes, I asked him and I asked him after noontime consumption, uh, also the same questions. And they were convinced that there was a plot to destroy them. And that was the primary reason.

RFA: And did you ask him about that part, about Tuol Sleng prison?

Thayer: I did. And he claimed that he"d never heard of it, and it was probably the most difficult part of the interview in terms of confrontation, because it was clear from the documentary evidence that he was, in fact, in charge of the Khmer Rouge killing machine. And he denied that … that he had ever heard of Tuol Sleng and that he had any involvement at all. But at the same time, he admitted to killing people but justified it as them being part of the Vietnamese plot to overthrow (them).

RFA: How was the interview atmosphere? Did he appear friendly to you or fearful to you? Secondly, how about the accuracy? How did you feel in that time? Did what he said sound reliable and accurate to you?

Thayer: He came across as very genuine. Like any top political leader, he had great charisma and I had great sympathy for him. He was an old man. He was sick. He was, in fact, dying. And that was quite clear. He was clearly trying to draw sympathy towards himself and his political movement to put into place in history the way he"d like it to be viewed.

RFA: Back to the evacuation of cities. Did they think about the consequences?

Thayer: No, they didn"t think of the consequences. And then that was one of the perennial problems with Khmer Rouge is that they only thought of the benefits and not the consequences to some of their actions. And they were absolutely concerned that there were enemies everywhere. There were enemies within the population, within their own ranks. If there were spies in the employ of foreign intelligence agencies that were trying to overthrow them. And they were absolutely convinced that the most important thing for them to do was to protect the leadership of their movement and to keep them in power and keep them safe and keep them from being killed. And they took every measure possible to ensure that without thinking of the consequences. And when they evacuated the cities, Pol Pot told me that that there were two coup plots in process at that time to overthrow them: one by Lon Nol after a meeting in Bali in May of 1997 and another from within the Khmer Rouge ranks themselves, and claimed six different coup attempts against him during his years in power. And he was absolutely concerned that there were enemies within the ranks, within the army, in the employ of the Vietnamese, and in fact, in the employ of all three, the KGB, the CIA and Vietnamese at the same time working together against them. In fact, it was his entire focus on the Vietnamese taking over Cambodia that created his policies, that created so much suffering within the country, that weakened the country so much that in fact allowed his worst nightmare to come true, that the country was so weak that it became vulnerable to a Vietnamese invasion. And it was his policies of terror and incredible suffering that, in fact, made the country weak enough to allow what he feared the most to come true. You could argue that it was Pol Pot who made Cambodia in a position to become a satellite of its historical enemy. And it was something that was, I think, almost too painful for him to accept himself, that it was his own policies that created the conditions that allowed Cambodia to disappear. When he, in fact, took credit for saving the country from disappearing from the face of the earth.

American journalist Nate Thayer sits bandaged in a hotel room on Oct. 15, 1989 in Aranyaprathet, Thailand, after he was injured in a land mine explosion while returning from Cambodia. Credit: Associated Press

American journalist Nate Thayer sits bandaged in a hotel room on Oct. 15, 1989 in Aranyaprathet, Thailand, after he was injured in a land mine explosion while returning from Cambodia. Credit: Associated Press RFA: Why didn"t the many reported coup attempts against Pol Pot succeed? What happened?

RFA: Why didn"t the many reported coup attempts against Pol Pot succeed? What happened?Thayer: Anyone who voiced any opposition to it, however small, even within the top leadership of the Khmer Rouge, was immediately deemed an enemy and arrested and killed. When the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, there were 22 members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. By the three years, eight months and 20 days before they were overthrown, 18 of those 22 were in fact killed and targeted to be killed by Pol Pot himself. The vast majority of the victims of execution of the Khmer Rouge were, in fact, Khmer Rouge cadre themselves, and it was the purifying of the forces within the Khmer Rouge that were the main targets of Pol Pot. For every one person executed, probably seven died of starvation or overwork, and the executions were targeted mainly among Khmer Rouge cadre. And it created an atmosphere of immense fear throughout the country that anything, any small thing that was done that might be perceived as being against the regime was tantamount to death.

RFA: What did you ask Ta Mok?

Thayer: Well, about, for instance, his involvement and knowledge of Tuol Sleng and taking responsibility for the great suffering that occurred during the years that he was in power. Ta Mok was an uneducated military commander, and he was a peasant and a military commander who spoke very straightforwardly. He was the first Khmer Rouge leader ever to acknowledge in an interview with me the fact the Khmer Rouge had, in fact killed hundreds of thousands and that he regretted it. And then it was it was a mistake and it was wrong. Although he denied any personal culpability. Duch was the first Khmer Rouge leader that I"d ever interviewed who in fact took responsibility for what he had done. He acknowledged thoroughly that he had been responsible for the deaths of thousands of innocent people and felt great remorse. And he was the only leader. And I interviewed all the Khmer Rouge top leaders who ever acknowledged that he, in fact, was responsible for the deaths of innocent people and was willing to admit it and willing to take the consequences of it.

A Khmer Rouge soldier waves his pistol and orders store owners to abandon their shops in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 17, 1975, as the capital falls to the communist forces. Credit: Associated Press

A Khmer Rouge soldier waves his pistol and orders store owners to abandon their shops in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 17, 1975, as the capital falls to the communist forces. Credit: Associated Press

RFA: Could you tell us a little bit about Tuol Sleng from what you learned about it?

Thayer: Well, Duch was very clear and many, many hours of interviews, very detailed and precise about the organization of S21. He reported directly Son Sen and to Nuon Che. Son Sen as the military representative within the Khmer Rouge and Nuon Chea as representing the Communist Party. And every interrogation that they made, documents were photocopied and sent to both Nun Chea and Son Sen. And Nuon Chea, took over the entire administration of S-21 in 1978 while the war was beginning to grow against Vietnam and such and went on to take control of leadership of the war against Vietnam. And it was very clear from Duch that Nuon Chea was directly responsible for the killings of thousands and thousands of innocent Cambodians and had no regard for interrogation processes or for any kind of even remote respect for human rights against his own people.

RFA How about the killings in Tuol Sleng?

Thayer: Yes he did. He went into great detail. And first the prisoners were interrogated, sometimes for many, many weeks, sometimes for months. And once they were finished of value of interrogation, they were taken to be killed at Chouerng Ek, seven miles from from S-21. And he made it very clear that it was the rules of the Communist Party, that anyone who was arrested would die, that there was no question about that anyone who was ever arrested would be killed. And he looked at the arrest of people from, I think, his scientific background as a mathematician, where he never questioned the correctness of the party, that anyone who was arrested was guilty. But those people arrested included the wives and children and family members. Duch was very remorseful. He broke down into tears about all of the women and children who he had ordered killed.

RFA: What would make him confess all these things to you?

Thayer: You know, Duch was a fanatic and he was a fanatic in his training as a mathematician, as a member of the Communist Party, and later, after the fall of the Khmer Rouge, as a born again Christian. And the tenets of fundamentalist Christianity are that in order to be saved, that you must confess your sins and you must seek salvation through redemption and confessing your sins. And he was a born again Christian, then a fanatic Christian. And he believed that in order for him to go to heaven that he would have to take responsibility for his actions. And that was, in my view, why he was willing to confess, because he thought that it was according to the Bible, that he would have to take responsibility for his actions.

A visitor stands before a map of Cambodia made from the skulls and bones of victims of the Khmer Rouge"s brutal 1975-79 "killing fields" regime at Tuol Sleng in Cambodia, June 23, 1997. Credit: Reuters

A visitor stands before a map of Cambodia made from the skulls and bones of victims of the Khmer Rouge"s brutal 1975-79 "killing fields" regime at Tuol Sleng in Cambodia, June 23, 1997. Credit: Reuters

RFA: Very few people made it out of Tuol Sleng.

Thayer: There were seven people out of 16,000 who survived, and those seven were ones that were left over when the Vietnamese took control. There were there were only two people that Duch ever freed. One was a Frenchman by the name of Francois Bizot, and another was a Khmer Rouge cadre who was misidentified. But Duch said repeatedly that it was the policy of the party. Whoever was arrested must be killed, and there was no question about that.

RFA: Is there anything else you want to add about these three important figures that Cambodian people should know?

Thayer: If we were able to contribute anything, it was that we were able to get some of the facts about what happened during the Khmer Rouge time. As a matter of public record and that the efforts of the press were far more successful than the efforts of any government to at least have Cambodians be able to have some knowledge from those who were in charge of those terrible years of suffering under the Khmer Rouge of what happened, and whether their leaders felt, in fact, any remorse or took responsibility for their terrible failed policies while in power.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

|

本篇 |

不想錯過? 請追蹤FB專頁! |

| 喜歡這篇嗎?快分享吧! |

相關文章

AsianNewsCast